With a GDP of $24 trillion and a population of 520 million, the EU and Britain are important drivers of the world economy. They have entered 2025 in a dire state, with Germany expected to be in its third consecutive year of recession, its worst performance since the Second World War. High energy and labour costs are threatening the competitiveness of large parts of the economy, with German industrial production about 10% below pre-covid levels. Other large economies don’t look much better: France and Italy are expected to grow their GDP by 0.6% this year, but are running mid-single digit budget deficits to get there. In Britain there were some hopes for growth after last year’s general election, but these have faded quickly, with the new Labour government expected to take taxes as share of GDP to around 38%, the highest in over 70 years. We may only exaggerate slightly if we say that the consensus view of Europe is one of an industrial museum with generous healthcare and pension schemes, nice beaches and picturesque towns. Certainly not a place to invest.

In September, Mario Draghi, the former president of the European Central Bank, issued a 400-page report, arguing that the EU needs to invest around €800 billion per year (c.4.5% of GDP) to improve productivity and growth. He also highlighted issues such as fragmentation and excessive regulation. The EU has 34 telecom operators, compared to three in the US. While the US produces one type of battle tank, the EU operates twelve. The EU needs corporates to innovate, but strangles them with red tape, passing 13,000 legal acts over the last five years. After Draghi’s report, there was some nodding in European capitals, but then the continent returned to business as usual.

After three events in February, we believe Europe is now on the cusp of real change. On February 14th, US Vice President JD Vance spoke at the Munich Security Conference, highlighting a supposed lack of democracy and free speech in Europe. The reaction was one of shock, with French news outlet Le Monde calling it an “ideological war on Europe”. A few days later, on February 23rd, Germany held federal elections. The result did not deliver any big surprises, with the centre-right and centre-left parties likely to now form a coalition under a new chancellor, Friedrich Merz. Merz is business friendly, but one would have hardly expected revolutionary changes under his leadership. The last important event was on February 28th, when Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelensky visited the White House, supposedly to put his signature under a mineral rights deal with the US in a first step to end the war with Russia. What unfolded was a shouting-match in front of a global audience.

After Vance’s speech and events in the White House, European capitals have begun to realise that the world order is changing and that they will have to step up for their own defence. Poland’s Prime Minister Donald Tusk noted that Europe is a giant that has now woken up. The EU is now considering looser deficit rules to allow for higher defence spending, a common defence budget, and countries are discussing a shared nuclear umbrella. Perhaps most striking, Germany’s incoming chancellor announced a “whatever it takes” approach to defence, ending years of fiscal restraint. Assuming the measures receive approval in parliament, the country would be expected to borrow an additional €1.5 trillion over the coming decade, equivalent to over 30% of GDP. Defence accounts for more than half of this, with most of the remainder earmarked for the country’s ailing infrastructure. Deutsche Bank called it “one of the most historic paradigm shifts in German postwar history” and markets agreed, with the yield on ten year bunds jumping by 30 basis points in a single day, the biggest move since the fall of the Berlin Wall. Deutsche Bank estimate that the package would increase German GDP by 2% over the next two years. Perhaps we may now also see labour market reform and de-regulation to drive lasting growth.

Another large stimulus to Europe could come from peace in Ukraine. The continent may then resume energy purchases from Russia, with even the US recently expressing an interest in reviving the Nord Stream gas pipeline. It is unlikely that Europe would return to its historic reliance on Russia, but even some relief would boost European competitiveness. Of course, the White House could throw a spanner in the works by raising tariffs on European imports, but it seems likely that the continent would then seek a closer relationship with Asian trade partners. We have learnt over the last month that the continent is not sitting still.

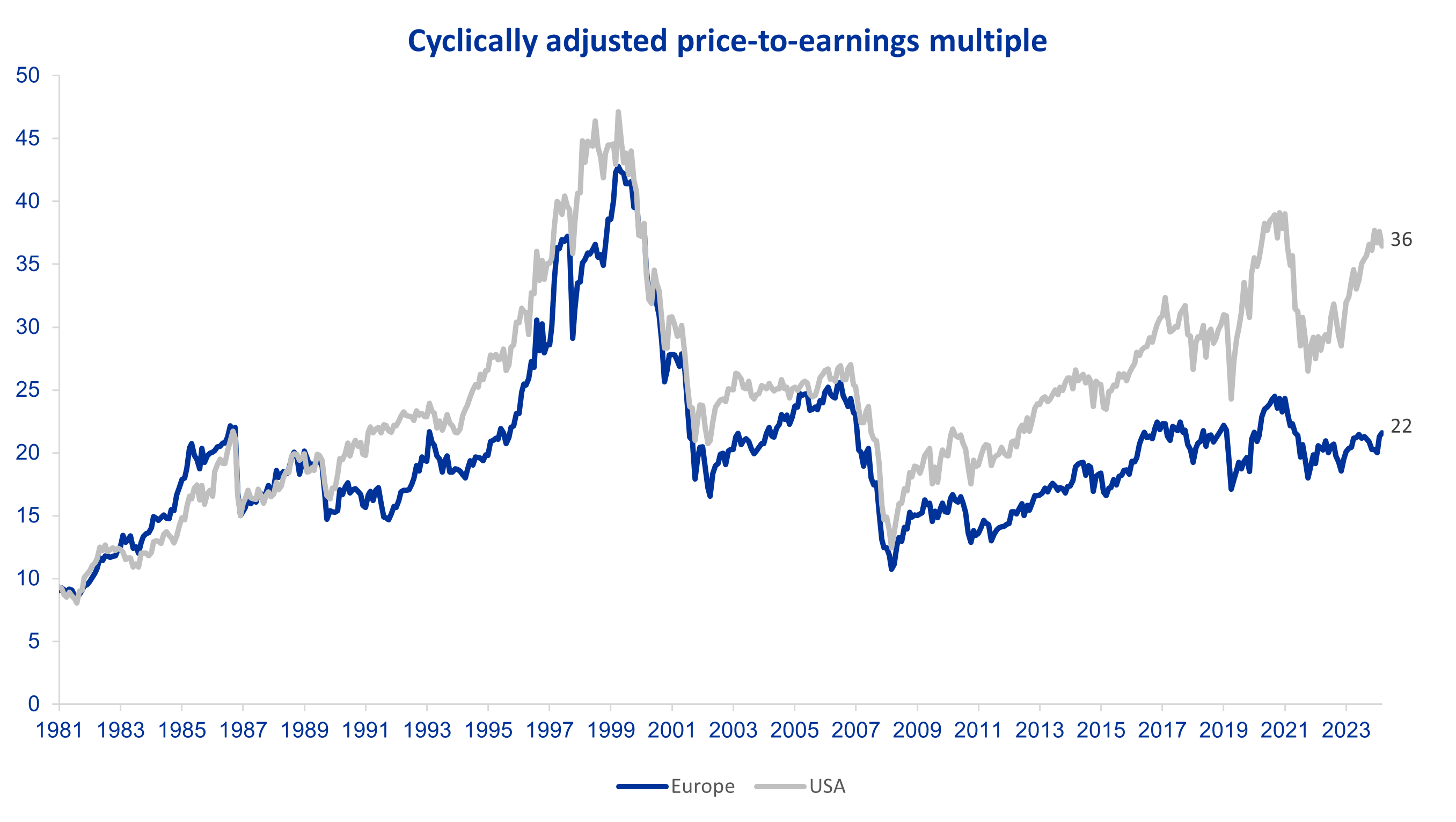

At Oldfield Partners we have never believed that Europe belongs in an industrial museum. Our portfolios are invested in many innovative companies across the continent, and we continue to find new ideas across the consumer and industrial space. We believe that politicians’ awakening will vastly improve their future prospects. Although European markets had a good start to the year, their cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings multiple continues to trade at a 40% discount to the US. Given the improving prospects, we believe the European market remains attractive on an absolute and relative basis.

Source: Barclays. Date as at 28th February 2025.